Concentration is the only way to out-perform the index, but it comes with a price…

Modern Portfolio Theory (MPT) in investing was introduced in 1952 by American economist Harry Markowitz. It was seen then, as it is still today, by some, as a groundbreaking way to measure and manage risk in investment portfolios which allows portfolio managers to achieve better returns for lower risk. The only slight problem is that it is complete rubbish.

MPT relies on financial mathematics in terms of estimating a number of different assumptions and back-testing a whole bunch of variables like correlation and portfolio variance. When done within mathematics and on paper it looks amazing; when tested in the real world, it completely falls apart.

One of the main reasons is it believes the Efficient Market Hypothesis, which says the current market price reflects all possible information about stocks and the market, ie the current share price is always the correct price. In contradiction to that, I can simply point to Facebook (or Meta as it now called) last week. On 2 February it closed at $323. On 3 February, after announcing earnings, it closed at $237.76 – a loss of 26% on the day – so much for perfect knowledge at all times.

As you’ve probably heard me go on about before markets are not efficient for one simple reason – it involves humans, and we humans are not always rational. The main problem is that we think we are being rational at all times, when clearly we are not. Economics has grappled with this issue in a similar way.

The other problematic principle around MPT is that it assumes the more diversification you have, the more you reduce risk. The principle around this is that certain assets – even different stocks within the same market – have negative correlations, which is as one goes up, the other goes down. The theory says if you can balance a portfolio with these assets, then you will outperform at the market when it goes through its usual up and down gyrations.

Again, when faced with the harsh reality of the real world, this falls apart. To be fair to this theory, it actually does work most of the time – the problem though is it breaks down at exactly the time you need it most – in extreme market stress environments. In these environments, as we saw in March 2020, the correlation of most assets goes to 1 – as in everything falls – because investors, and more importantly risk departments at fund managers, panic and there is forced selling of everything.

“So what?” I hear you ask. How does this impact what I’m doing and how I invest?

Well, this feeds into how we make recommendations here at Permanent Wealth Partners and it follows one of two paths. For many of our clients, we simply stick with low-cost index investing. Why bother to try and beat the market at its own game, when you can simply own the market. It’s simple, it’s low-cost and it consistently achieves very strong results over a long period of time. Great. That process is suitable, frankly, for most investors.

However, there are other types of investors who believe our approach that markets are not efficient and above-average gains can be made. The only way this can be done is through concentration of investments – the exact opposite of diversification. By concentrating on individual stocks, or in our case sectors, we are taking a view that those assets will outperform the general market. If you have too many of these, then you become more and more like the market and the job becomes tougher.

It’s also not just us that thinks this way. Terry Smith, the Fundsmith manager, writes extensively on this topic and even includes a chapter in his book called “Too many stocks spoil the portfolio”.

Charlie Munger, Warren Buffett’s right-hand man, has a famous quote that says, “Any idiot can diversify”.

Baillie Gifford, the active fund manager, also pursues this concentration theory in most of their funds.

The key part, obviously, if you are going to run concentrated portfolios, is getting it right. And this is where the ‘price’ that I refer to in the title comes in. If you do get the choices right, then you will have sizeable outperformance. However, as we all know, markets do not always do what we all think they should do, and there are periods of significant underperformance.

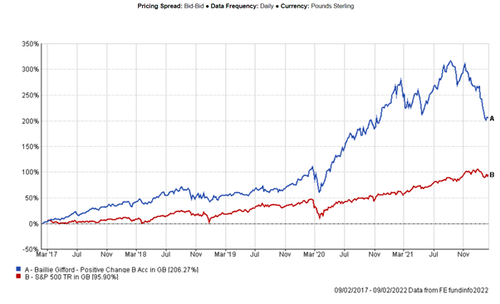

The table and chart below are of Baillie Gifford Positive Change – a fund that we are happy to recommend to clients. It runs a concentrated portfolio of companies (as shown below) that the fund managers believe are going to change the world in a positive way. Lofty and noble expectations and over time it has done very well.

However, if we zoom into the last three months since November, you can see the significant underperformance vs the S&P500 Index. In this case, the concentration has hurt fund performance because of the style shift of what has been working within markets.

Does it mean the fund managers are bad and wrong in their view? No.

Does it make us review our recommendations and cause concern? Yes.

From a long-term perspective, our view is that this fund still has companies that will produce higher than market returns. However, it will go through periods like we’ve just been through. And this will happen over and over and over again.

This is the ‘price’ of concentration I refer to. Done properly, you should achieve above-average returns in the long-term, but these funds will all go through periods of underperformance when the market-style shifts. It will be uncomfortable, but to achieve higher returns, this is necessary.

If that’s not for you, or you find it too stressful, that’s fine – there is nothing wrong with being an index investor either.

Incidentally, Harry Markowitz is still alive today, aged 94. Perhaps that’s the best advertisement for index investing there is!