We need to talk about… bonds

I’m not ever going to discuss penny stocks or Wallstreetbets punting stonks – I’m far too sensible for that – but here’s one I couldn’t resist.

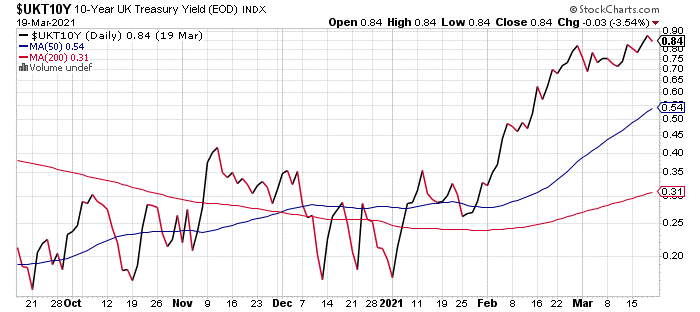

I’m talking about an asset that started the year (1 Jan 2021) at 0.20 and is currently trading at 0.83.

Looks like pretty amazing returns doesn’t it? Can you guess what this is?

Bitcoin or some other crypto nobody has ever heard of? Gamestop? Some small pharmaceutical company that is involved in vaccines or testing?

The answer is no to all of those.

The answer, bizarrely enough, is the yield on UK 10 year government bonds.

This may be slightly disingenuous – as you can see above the rate does tend to bounce around a lot (like in November it was 0.4%) and this is an interest rate, not a price. So, yes. I admit – I’m using slightly poetic license to make my point.

But my point is there has been a very large move in rates which has direct implications for most people’s portfolios. And this may be just the beginning.

Just an aside to clarify a couple of definitions.

When I’m talking interest rates here, I am not talking official Bank of England rates. This official interest rate is still 0.1% and this is the rate that the UK Government sells it bonds at.

What I’m talking about here is the ‘market’ rate or yield. So once these bonds are issued to buyers, they have a market value which is based on the known returns in the future when compared to future expectations of interest rates or yield. The yield also equals the fixed interest rate of the bond divided by the market price. If you want a further discussion on this, I can bore you with many details.

But, the key points around this definition are:

-

Future interest rates expectations are driven by inflation, or the rising of prices; and

-

If expectations of rises in prices increase that means a rise in yields. As yields increase that means the market price of the bond is falling. And that is not great for bond investors.

So why does this matter?

Because without realising it, you are probably a bond investor somewhere.

Let me explain…

Our financial regulator is wonderful. Of course I’m going to say this. However, there are some things I think they make a little too easy, that allows pension companies, advisers and IFAs to just follow the letter of instructions without actually thinking about what they’re doing.

A risk questionnaire is a prime example. Anyone who knows anything about questionnaires knows the response range is normally based on a normal distribution. That’s just human behaviour. People tend to respond to questionnaires with answers around the middle.

The problem with this approach is that it pushes people generally towards a moderate or balanced risk approach. A typical balanced portfolio is 60% equities and 40% bonds (or other supposedly non-correlated assets).

Now, in general, there is nothing wrong with that, but its very easy for an adviser or IFA to say “here you go, you’ve ticked the boxes, you’re a balanced investor, here’s a balanced portfolio for you, thanks very much, job done” without considering anything more.

It’s lazy, it’s bad financial planning and it’s dangerous for wealth. And I see it all the time. All the time.

Even worse are the billions pumped into employer pensions each year, especially for young people, where most tend to end up with the default balanced funds because the whole pensions thing is so confusing for any normal person.

This is really dangerous and means people’s long-term financial wealth will be most likely lower than it otherwise would be.

Why? Well let me sum up my ramblings in one quick sentence.

If we are expecting inflation to pick up and interest rates to rise further, at this point bonds make a terrible long-term investment.

However, this does not necessarily mean they shouldn’t be in your portfolio. You may prefer stability in the short-term for money you may need to access over the next 5-10 years, so that gives a good justification for including them. I should also add, that one bond is not the same as the other. Government bonds are different to corporate bonds which are different to index-linked bonds and the list goes on. So there are plenty of caveats.

But my point is that interest rates are very low right now and have just started to increase. This is an interesting and noteworthy move, hence it has my attention.

How high can rates go?

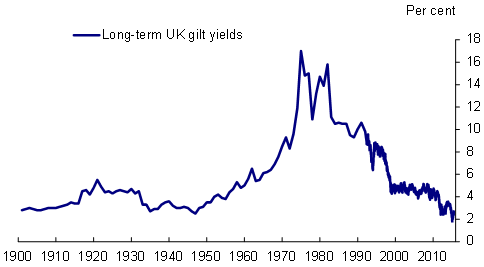

I think this chart is very interesting, though not for the obvious reasons.

Excuse the simplistic Excel version of this chart – however it gets my point across. Obviously interest rates can go up to 17% – 18% as they did in the 1970s and 1980s. I remember my parents complaining about 15% mortgage rates.

But, what I found more interesting from this was the spike in yields in 1920, just after WWI and, drum-roll, the Spanish Flu pandemic. This was the start of the roaring 20s where suppressed creativity and joy were unleashed and, unsurprisingly, we saw inflation pick up a bit with Gilt yields above 4% for basically all of the 1920s.

The prime reason around this was not only the increase in consumer spending but also capacity constraints created by an economy on a war footing that needed to re-adjust to civilian life. Would this be a surprise if something similar happens now?

And also take a look at when inflation took off in the 1940s. That was just post WWII with a similar scenario described above.

As we all know, history never repeats, but it does sometimes rhyme. I found this really interesting and here’s another example of a personal anecdote that is close to my heart.

What will a pub charge for a pint (or insert your desired choice of entertainment) before people stop buying? Will a pub (or concert venue or sporting stadium or theatre) be justified in putting up prices to make back some of the lost profits of being closed? I think most people would probably say yes. So they’ll probably pay. That is inflation.

And that pushes inflation expectations higher in the future. And that is bad for bonds.

I’m not advocating a large-scale shift out of all bond exposure here. I just want to raise the topic and discussion point that for any long-term holdings – for example, pensions – perhaps it’s time to review again the prescribed risk levels on a time-frame basis – something that we do with all of our clients – and make decisions that will be beneficial for your long-term wealth.

Adam Walkom

##The above is not personalised financial advice. Please get in touch to see how the above impacts your personal situation.##